The „Hakenkreuz“, originally known as a swastika, is one of the oldest symbols of humanity from the series of lucky symbols. It spread to large parts of the world from the Neolithic Age and is still in use today. Although it is banned in most European countries due to its use by the Third Reich between 1933 and 1945, it is still very popular, especially in the Buddhist strongholds of East Asia. In Japan, inspired by manga culture, it is even becoming a popular symbol of youth language in the sense of ‘absolute’.

Closely related to the four-pronged swastika are round shapes and various three-pronged symbols.

The earliest swastikas do not appear in northern Europe, but in southeastern Europe: in a strip that extends from present-day Hungary through Romania to Serbia – or even further east, if one recognises the symbol from present-day Ukraine as a swastika. At first glance, it does not seem very likely that the swastika was first used almost 10,000 years before it first appeared in today’s Ukraine. However, the reference to a bird is certainly in line with the most meaningful derivation of the symbol from the sun. Various birds are considered a symbol of the sun, including the eagle, whose name ‘Ar’ corresponds to the Old Norse word for sunlight, Ar. The ‘light sons of the sun’, the Aryans, introduced the eagle as a coat of arms into various regions of the Mediterranean, where it was preserved for a long time as a symbol of the nobility and still adorns various coats of arms today. At the same time, they also carried the swastika symbol with them. In addition, the eagle was also considered a ‘fire bearer’, synonymous with the symbol of lightning, which once brought fire to earth.

Alongside the eagle, the swan, the companion of the sun god Apollo, is also a solar symbol. As the symbolic animal of the sun-god, it came from the north to the Mediterranean region with the Nordic Sea peoples, where the sun-god found worship as the son of Apollo. The swan is the classic polar animal, pointing to a hypothetical homeland of the Nordic peoples in a subarctic region. The idea of the bird as a symbol of the sun is connected with the idea of the bird as a ‘bearer of souls’. The soul bird, which takes up the soul of a dead person, already appears in the Upper Palaeolithic period. In the megalithic period, when the corpse was laid out on the grave at the beginning, birds were regarded as soul messengers. Riding on the rays of the sun, they take the soul away and return with it to the newborn. This is also the origin of the idea of the stork as a bringer of children.

There is no doubt that the swastika was also associated with the sun in its early centre in the area of the Danubian culture (Vinca culture), which is considered to be one of the earliest advanced civilisations in Europe. Its course meant winter extinction as well as spring rebirth of nature with its accompanying phenomena. Things that could only be perceived and processed in cultic form in the extreme north, namely in the form of the sun cult and its symbol, the swastika. According to Herman Wirth, this embodies ‘the great certainty of salvation from the divine world order, the eternity of being, the renewal of life that is from the light of God. It expresses what the Aryan Indians called rta (from the Latin ritus, our word art, etc.), the rotation, the circulation, the cosmic world order, the world law, the civilisation, the divine right. Those who stand in these divine laws of all existence have the renewal of the life of God in the chain of existence, their clan, which comes from God.’

But why is the swastika nevertheless associated with fire or the fire whirl in some cultures, for example among North American Indians, where it is known as the ‘swirling roundwood’?

The idea behind this is that fire is a component, or rather a child, of the sun; fire is the earthly embodiment of sunlight. The ‘holy’ fire was ritually rekindled at every solstice celebration. At this point, sun and fire worship merge and thus also influence the symbol of the swastika. The roots of these ideas, of the sun and fire cult, undoubtedly lie in the far north, where the sun disappears in winter before reappearing in spring.

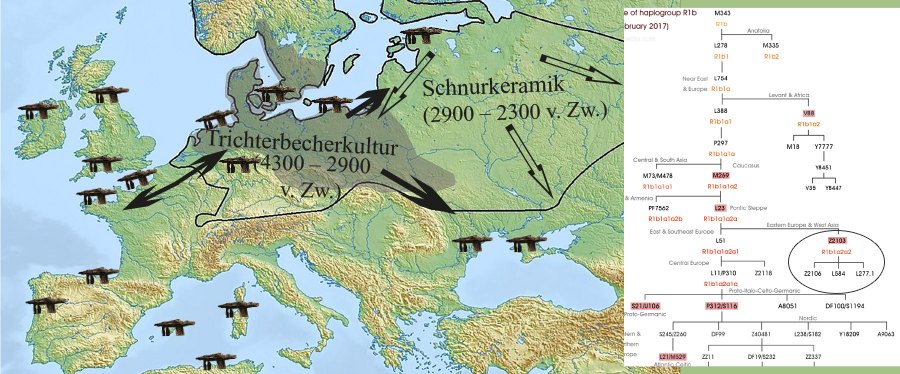

So does the symbolism of the swastika also come from the north? There are at least indications that the Vinca culture originated from a superimposition of settled farmers by mobile groups of hunters from the north. In any case, the swastika only appears after the northern movement of the band ceramicists around 5500 BC, and could therefore also come from the north. There are also indications of migratory movements from Northern Europe to Southeastern Europe for an earlier period around 10,500 BC, which could have made a cultural transfer possible.

Even if the source material for the assumption of a Nordic origin of the swastika is thin, the swastika can undoubtedly be stated as a ‘Nordic symbol’ on the basis of its history. The name stem form is Indo-European and is composed of the syllables ‘thu’ and ‘ask’ — so it has the same origin and the same meaning as the name of the god Tuisko. In its various forms, it appears in the Neolithic Age wherever people from the north settle. The swastika has been found in Troy, India, Persia, China, Japan and even North and South America, as well as in Egypt and Mesopotamia.

But unlike in Europe, the swastika disappears in other parts of the world until it comes to a – this time obvious – north-south transfer: at the end of the Bronze Age, the swastika comes from northern Europe, where it appears in the form of Bronze Age rock carvings, across the Alps and the Val Camonica – again – to the Mediterranean.

The picture shows the Swastika of Ilkley-Moore (Great-Britain)

Excerpt from ‘The Swastika’

[order here (german language)]