There are authors who want to enable their readers to gain new insights, to take them on a journey through new literary or scientific territory. And there are authors who want to indoctrinate readers with propaganda, to instil in them the thoughts that move them. Among the latter are the freelance author Thomas Trappe, who only recently denied the existence of entire peoples on his blog, and the biochemist Johannes Krause, who, as director of the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History in Jena, is one of the leading archaeogeneticists in Germany. Krause is undoubtedly an expert in his field: he was involved in decoding the Neanderthal genome and, in 2010, he and his colleagues discovered the new prehistoric human form of the ‘Denisovan’ using genetic analysis. But there is also the ideologue Krause. In August 2020, Krause was one of the initiators of the Jena Declaration, with which the German Zoological Society left the path of science and described race as ‘the result of racism and not its prerequisite’ and advocated the removal of the concept of race from the German constitution.

A few months earlier, the ‘Christian Drosten of archaeogenetics’ published the book ‘The Journey of Our Genes’. The book is presented in an unscientific manner and is primarily intended as a political tract: ‘It should be noted that this book is intended,’ the author duo reveals, ‘not only to address political controversies, but also to summarise the findings of archaeogenetics on the history of Europe for the first time…’ (p. 10). The core message is already apparent in the opening credits and in the individual chapter headings. Without the immigrants who came to Europe from all directions over thousands of years, repeatedly bringing innovations with them, our continent would be inconceivable; indeed, without migration, we would not exist.

Although interesting facts do appear, such as the reference that the switch from hunting to agriculture brought with it many disadvantages, the trained biochemist makes mistakes not only in archaeology, a field conspicuously foreign to him, but also in his own profession: for example, the claim that the genetic makeup of an ancestor ten generations back is ‘highly unlikely to be detected in a current genome’ (p. 36) is false. In fact, the probability is about 50%. The sentence according to which the ‘genetic components of farmers and hunters and gatherers almost completely disappeared 4800 years ago’ is also simply incorrect. It was only their proportion that decreased compared to graves that contained more eastern genetic material, which is attributed to eastern hunters and gatherers (‘Eastern Hunter Gatherer’ – EHG).

Ethnicity not genetically verifiable?

Krause’s claim that we do not carry any genes that identify us as ‘members of a particular ethnic group’ or even a nation seems particularly remarkable, although he himself admits exactly this at one point in his book (p. 36): ‘The closer people live to each other, the closer they are related… If you plot the genetic distance between Europeans on an X and Y axis, these coordinates are congruent with a map of Europe.’ But that is precisely what makes it possible to assign a person to an ethnic group or nation with a high degree of accuracy. However, this has nothing to do with indigenous peoples, although the last major genetic shift occurred 5,000 years ago. In order to save his self-questioning assertion of the non-existence of peoples and ethnic groups, Krause chooses the example of colours, of all things: and thus lays an egg in his own nest: for although the colours merge into one another at their edges, no one would claim that colours do not exist. On the contrary: the different colours are just as much the starting point for mixing as unmixed breeds are the starting material for later breed mixes, especially in Europe – but this makes it clear that breeds do exist after all.

Light skin due to agriculture?

Krause makes several errors in reasoning when he claims that the people from Anatolia who brought agriculture to Europe (‘Early Neolithic Farmers’ or ENFs) had ‘much lighter skin’ than the locals they displaced. Krause’s circular reasoning: ‘In contrast to the hunter-gatherers, they hardly consumed any vitamin D from fish or meat, but instead ate an almost exclusively vegetarian diet, supplemented by dairy products… Thanks to their lighter skin, they were able to produce the essential vitamin D, which was missing from their diet, in their own bodies – through sunlight.’ First of all, the Scandinavian Hunter Gatherers (SHG), who were not displaced at all, were significantly lighter in skin colour than their southwestern cousins, the Western Hunter Gatherers (WHG), and even lighter than the immigrants from the Mediterranean (ENF), who had only one gene sequence responsible for fair skin colour. In addition, due to the high level of solar activity in Anatolia, lightening the skin to produce vitamin D was only necessary to a limited extent. This is different in Northern Europe, where the sun shines far less and much weaker and lightening the skin is absolutely necessary for vitamin D production. If the transition from hunting to agriculture led to a lightening of the skin all over the world, then we would have to find many light-coloured populations worldwide, regardless of the immigration of Europeans, which is not the case.

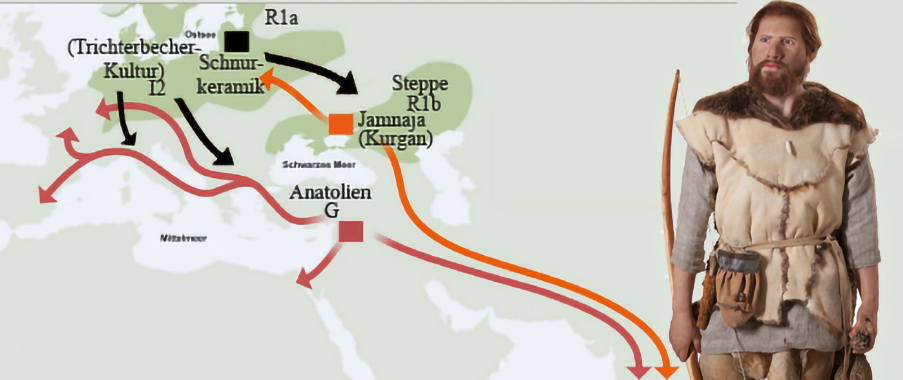

Steppe myths

Krause is in good company but still on the wrong track when it comes to interpreting the emergence of the Funnel Beaker culture around 4300 BC. This is considered to be the first northern European farming culture and was associated with the construction of megalithic or ‘hunebed’ monuments. ‘The long-established hunters and gatherers of Scandinavia were not displaced by the newcomers, but this was not due to their particular resistance to foreign influences, but on the contrary to an openness to the imported techniques.’ So even the wheel, which ‘the early Scandinavians knew,’ appears to have been imported. At least the author acknowledges that the Scandinavians invented the ‘early tractor,’ in which two cattle were yoked to a plough. In fact, it can be assumed that the warlike hunters from the north, the area of the Ertebolle culture, overlaid the band-ceramic farmers. In the male lines of the Funnel Beaker people, therefore, the old European I2 haplogroup predominates. Overall, however, the genetic composition shifts in favour of the Anatolians. Krause makes the same mistake with regard to the supposed invasion from the steppes around 3000 BC. This is made up of a series of improbabilities and absurdities and was archaeologically dismissed a long time ago, since all the alleged imports from the steppes were already known in Northern Europe before that. The semi-nomads from the steppes are said to have built large cities, which they only inhabited for half of the year. They are said to have known and worked with bronze, but to have forgotten it somewhere on the way to Europe. They are said to have had physiognomic features that would have been described as Nordic in the past, and to have developed the Indo-European language, which knew a great many terms for agriculture, water and shipping, although none of this played a role in the steppes. They are said to have migrated simultaneously to Northern Europe, Central Europe, the Balkans and also to the east. But the Indo-European language only arrived in Northern and Central Europe; in neighbouring Anatolia and Iran, it took more than 1000 years for the Indo-European language to catch on. So there must be another explanation for the strong increase in genetic potential from the east (EHG or Y-haplogroups R1a and R1b). The most likely explanation, not discussed by Krause: From the northeast, the eastern Baltic region, a westward movement of people took place who were culturally closely related to the northern Europeans and also brought with them the Corded Ware culture, which can be derived from the Funnel Beaker culture. Even though it is currently considered the standard work in archaeogenetics in the German-speaking world, in view of the strong propagandistic tendency in the service of one-world propaganda, we can only advise against buying it.