The remarkable interpretation of Homer by an Italian author

Tell me, Muse, the deeds of the much-travelled man who, after the destruction of holy Troy, wandered so far, saw the cities of many people, and learned their customs. And who endured so many unspeakable sufferings at sea to save his soul and the return of his friends. But he does not save his friends, however hard he strives; for they brought their own destruction upon themselves through their misdeeds: fools! who slaughtered the cattle of the high sun ruler; behold, the god took from them the day of their return. Tell us a little about this, too, daughter of Cronion.

With this invocation of the muse, the Greek poet Homer begins his ‘Odyssey’. It is the story of the king of Ithaca and his long and adventurous journey home, which, after the ten-year Trojan War, only allows him to reach his homeland another ten years later. Shipwrecked by adverse winds, Odysseus, whose companions have all fallen after many adventures, wanders through the world as it was known at the time, until he finally returns home unrecognised as a beggar. Here he has to assert himself against a number of suitors of his wife Penelope, who believe him to be dead.

After generations of pupils and students had learned these verses by heart until the middle of the 20th century, interest in the important epic has increasingly waned in recent times, even though the existence of the city of Troy was only scientifically proven a few decades ago where the German amateur archaeologist Heinrich Schliemann found it in 1870. At least, that is the official doctrine, as advocated by archaeologist Manfred Korfmann (†) and other leading scientists. Not uncontested: the list of those who see only a small settlement in Anatolian Troy, which could by no means be described as Homer’s Troy, is long.

A few years ago, an archaeological outsider joined the ranks of the critics, and he could give new impetus to interest in Troy, especially in German-speaking countries. For the Italian physicist Felice Vinci, it is not just a question of whether the settlement of Hissarlik excavated by Schliemann could be Troy, but rather the fundamental question of whether Homer, when writing his epics, did not have a completely different geography in mind, even if he was said to have been blind:1 namely, not the Mediterranean region, but the area of the Baltic Sea between Denmark and Finland. Homer himself was not a Greek or a Mycenaean, but a Scandinavian. In the middle of the second millennium, due to climatic conditions, a large proportion of Scandinavians are said to have emigrated to Greece, taking with them the epics of their Nordic homeland.

What at first glance appears to be abstruse becomes more coherent on closer inspection: Tacitus, for example, mentioned the contemporary view that Odysseus ‘had been shipwrecked in the northern ocean during his odyssey’ and ‘visited the lands of Germania’. Asciburgium, a place on the banks of the Rhine that is still inhabited today, was founded and named by him; it is said that an altar dedicated to Odysseus was found there, on which the name of his father Laertes was also written, and that there are still grave monuments with Greek characters in the border area between Germania and Raetia.What are Vinca’s main arguments?

He starts with the inconsistencies in the geographical descriptions of the world of the Iliad and the Odyssey, which have been noted by many researchers: For example, the often-mentioned Greek Peloponnese is not a flat island, as is repeatedly emphasised, but a very hilly peninsula. The island of Pharos at the entrance to the port of Alexandria is not a day’s journey from Egypt, but only a few minutes; finally, Dulichion, the long island off Ithaca, could not be identified in the Mediterranean region. Vinca’s conclusion after years of study, which he proves with numerous examples: The Homeric setting is the Baltic Sea region: the Peloponnese can be found on flat Zealand in Denmark, Dulichion is actually Langeland, Ithaca is Lyø, the river Aigyptos is the Weichsel and Pharos is in reality the island Farø; the true Homeric Troy is finally said to be the southern Finnish Toja, which, unlike its Anatolian counterpart, which was later called Hissarlik, retained its old name.

According to Vinci, Scandinavian emigrants in the mid-2nd millennium BC not only took the history but also the place names from their homeland with them and transferred them to regions in the Mediterranean. Proving this is difficult, although the names in use today in the Mediterranean actually come from the Greeks, who replaced older local names with them.

The transfer of names from their homeland to the new settlements was also a common practice among the Germanic peoples, as Hermann Zschweigert notes with regard to place names in the Alps. These can also be found in Norway, from where they were brought.3

If we now compare the Baltic Sea region with the section of the Mediterranean where the Odyssey was previously located, a striking similarity immediately becomes apparent. According to Vinci, the Nordic immigrants used these similarities to name the places in the same proportion as they were located in their homeland. Only the dimensions, distances between individual points and geographical details of the Homeric tales prove the original homeland in the Baltic region.

Further arguments of Vincis refer to the predominantly rough climate of Homer’s world, with a lot of fog and cold, as well as the possibility of fighting battles at night. This would not only be unusual in the Mediterranean, but almost impossible, but not in the far north during the summer, when the sun never sets completely. In addition, the ships of the Achaeans, described as having a double prow, reminiscent of later Viking ships. These could be rowed in both directions, as Homer also reports.

A convincing indication also arises from the comparison of Homer’s reports with the traditions of the Danish author Saxo Grammaticus: for example, the description of the circumstances of Hamlet’s life in the third book, which is strikingly reminiscent of Odysseus. In addition, there are further passages that are almost literally the same in both authors – a clear indication of a common Nordic source. Saxo also provides the explanation of the Hellespontians, who were searched for in vain in the Mediterranean region: they lived on the eastern coast of the Baltic Sea, in present-day Lithuania, on the actual broad Hellespont, which is known as the Gulf of Finland.Weaknesses of the theory

Several points in Vici’s coherent presentation are problematic, however: The similarities in names and the author’s references to a Nordic origin of Homer’s heroes do not in themselves provide any evidence for a Nordic homeland of the epics of Homer – only for the original origin of the protagonists‘ ancestors in Northern Europe. Above all, however, there is a lack of convincing archaeological finds, which are urgently needed to verify the thesis – but this would be a requirement that is more likely to be addressed to archaeology. After the long-dominant archaeological finds such as the Swedish Kivik grave (13th century BC) or Danish bog finds, an Early Bronze Age city has now been discovered in Bjastomon, northern Sweden, but it has yet to be thoroughly researched. In addition, a larger battlefield from the end of the Bronze Age has recently been made available to archaeologists in the Tollensetal in Mecklenburg. Both find complexes could support VINCIs theses in the future.

A greater difficulty is presented by the compatibility of the self-contained habitat of the Nordic Bronze Age, which included the Baltic Sea as well as large parts of the North Sea, with Homer’s description of people and the environment of some of the hero’s destinations: Thus, the Cimmerians, the ‘miserable men’, are said to be covered by a terrible night (11. G. 11-19), although this should be a familiar image to an observer living on the Baltic Sea. The land of the Phaiakes also seems strange, although it was part of the Nordic Bronze Age world. However, Homer also has the king of the Phaiakes state that they are ‘closest to the Danes in blood and descent’. If the Phaiakes were highly likely to have lived in the North Atlantic, then this quote seems to confirm Vici’s thesis that the entire narrative strand was settled in the North Sea-Baltic region.

However, the poet’s description of the weapons of the Achaean heroes raises further questions, as these correspond to Mycenaean conditions, while the Nordic Bronze Age differs from them: here, round shields prevail instead of the man-high tower shields that Homer describes in terms of Agamemnon’s armour. The mention of sails is another reason to doubt Vinci’s thesis, not to mention the lack of evidence of such sails in the Nordic region before the Christian era. This deficiency, which is particularly supported by the reference to Bronze Age boats depicted in rock paintings in Sweden, could be explained by the fact that the mast of these boats was removable, as Homer himself reported.

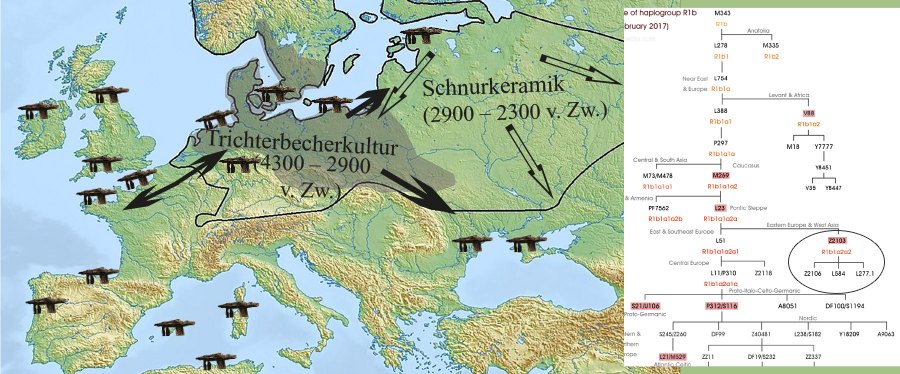

The author undoubtedly makes a mistake with his idea about the time when Homer’s northern European relatives, together with the orally transmitted epics, came to the Mediterranean region. Vinci assumes the mid-16th century BC and links this with the beginning of the Mycenaean culture, which is indeed set for this time. However, the researcher, who is not an expert in the field, overlooks the fact that the Mycenaean culture developed from the Pre-Hellenic culture, which was already established in what was to become Greece at the beginning of the 2nd millennium BC. It is true that these ancestors of the Mycenaeans also came from Europe, which explains the blond hair and light eyes of Mycenaean gods and heroes, as da Vinci rightly emphasised in his argument; but at the time of the emigration they could not have brought experiences of the Bronze Age with them. As early as 2000 BC, these Indo-Europeans were establishing settlements in central Russia. A few decades later, these ‘Aryans’ can be found not only in what would later become Greece, but also in Anatolia, where they became known as the Hittites, and even in China. Here they are the Tocharians, some of whose members in the Taklamakan Desert have been preserved for posterity. These mummies prove that their homeland must have been in northern Europe.4

Author Gert Meier, for example, attributed to the Achaeans, together with the later Persian Achaemenids, a common original homeland on the east coast of Jutland, Denmark, on the basis of the similarity of their names and their culture.5

The incorrect dating of the emigration of the Bronze Age epics is not, however, a fatal blow to Vinci’s complete thesis.

There remain three possibilities as to how the Nordic epics reached the Mediterranean region after Vinci: around 2000 BC with emigrant tribes that later founded the Mycenaean culture. In the middle of the 2nd millennium through proven contacts between the Nordic and Mycenaean worlds.6 Or thirdly only around 1200 BC, which would have been more likely if Jürgen Spanuth’s research were taken into account. He described migrations of so-called North Sea peoples who reached as far as Egypt and settled along the Mediterranean coasts. This enormous process at the end of the Bronze Age was reflected in the Egyptian (pictorial) traditions of Medinet Habu and in the Atlantis report by the Greek poet Plato. In Greece, the immigrants became known as the Dorians, who are considered the founding fathers of later Hellenic culture.7 Thus, the Homeric epics would have reached their new homeland at the end of the Bronze Age, possibly even with the ‘blind singer’ himself, who must therefore have lived in the 12th century BC. This would nevertheless explain why no data whatsoever was known about the ‘greatest of Greek poets’, about whom the Greek historian Herodotus claimed that he lived in the 8th century.

Joachim Latacz’s realisation that the language used by Homer points to an origin between 1500 and 1200 BC also corresponds to this assumption. However, this in turn conflicts with the knowledge of the Achaeans and Danaeans that can be proven among the Hittites and Egyptians before 1200 – two designations used by Homer for the attackers of Troy, who thus settled in the Mediterranean region before 1200.8Conclusion

Whether all the events of the Odyssey and the Iliad were actually transferred from the Baltic region to the Mediterranean world, or only some of them, which were mixed with other indigenous Mediterranean traditions to form a narrative thread, is a question that future scholarship will have to clarify. In any case, Vincis’s research is of outstanding value, as it raises the possibility that the Nordic world of the Bronze Age will gain even clearer contours. Undoubtedly, it is worthwhile to examine the thesis more closely from an archaeological point of view. At the same time, Vincis’s work could provide explanations and evidence for some of Jürgen Spanuth’s theses, especially with regard to the origin of some North Sea peoples. For example, the origin of the Philistines from Crete, which is predominantly represented today – according to the self-declaration i-kaphtor = from the land of columns – would be very well explainable with the descent from the Nordic name patron in Pomerania. It would also now be understandable why the Achaeans were also called Danaeans in Homer – a name that clearly indicates the Danish homeland of these people. Furthermore, Vinci’s theory would make other sagas comprehensible: according to tradition, various Germanic tribes descended from the Trojans. In the 7th century, for example, the chronicler Fredegar reported that the Franks were once ruled by King Priam in Troy before they set out under Fridigas and founded a second Troy on the Rhine, which is identified as today’s Xanten. This city, directly adjacent to Asburgium (Mörs-Asberg), which Homer mentions as Ulysses‘ destination, was still known as “Little Troy” in the Middle Ages.9

A similar saga relates the founding of Rome by the Trojan exile Aeneas, who, according to the account of the Roman author Virgil, first came to Thrace after the Trojan War, then to Crete and Phoenicia, and finally founded the city of Rome in present-day Italy. According to Spanuth, Thrace, Crete and Phoenicia were the targets of the attacks and settlements of the northern Sea Peoples around 1200 BC. And indeed, the Italics, as the progenitors of Rome, also migrated to Italy from the north around 1200 BC.10Notes:

1) Possibly the term ‘blind’ was used for Homer merely as a synonym for his gift of foresight, his perspicacity, as Alain de Benoist notes in ‘Aus rechter Sicht’ (Tübingen 1981).

2) Tacitus: Germania 3,2.

3) Zschweigert, in: ‘Deutschland in Geschichte und Gegenwart’ No. 2/1993, p. 38. The example of America also still bears witness to this custom, which can be observed in all Europeans (New York, New Amsterdam, etc.).

4) An illustrated report can be found in BdW 9/1999, p. 40 ff.

5) Cf. Meier, Gert: Did the Persians come from the Baltic Sea? In: DGG 4/2004, p. 41.

6) The Achaean character of Homer’s world, which does not know writing, simple living conditions and still stone clubs, speaks for the time around 2000. Cf. Hans-Peter Dürr: The Argonauts‘ Voyage.

7) See Jürgen Spanuth: Die Atlanter. Volk aus dem Bernsteinland. Tübingen 1976. However, Vinci believes that Homer’s language is more similar to Ionic (from 1600 BC) than to Doric dialects (from 1100 BC).

8) Joachim Latacz: Troy and Homer. TB 2nd ed. Munich 2004, p. 166 f.; also the obvious assumption that the Paris/Alexander mentioned by Homer is identical to the king referred to as Alaksandu in a Hittite treaty (ibid., p. 131 ff.) makes it difficult to accept an exclusively northern European tradition.

9) Cf. Dr Reinhard Schmoeckel: The Troyan Legend in the Early Franconian Sources. In Trojaburg 1/2006, pp. 34 f.

10) Jürgen Spanuth: The Atlanteans. Tübingen 1976.